Hiding and Being Seen

It's springtime in Georgia, and my neighborhood is awash in blossoms. As the earth warms, and the angle of the sun shifts, the trees have no choice but to bloom, displaying their vitality for all to see.

I am grateful for their beauty. And this season of reflection, with Passover on the way, reminds me to be grateful, too, for my freedom. What does freedom mean to me? I have had some recent opportunities to engage deeply with the notion of freedom and to consider its presence in my life and its potential for absence, in my life and in the lives of others.

I've written before about the special nature of my synagogue, Congregation Bet Haverim (CBH) in Atlanta. CBH was founded in the 1980s by gay and lesbian Jews who were seeking a safe place to worship and be in community with each other. They added a "Prayer for the End of Hiding" to their liturgy which affirms the rights of gay and lesbian Jews to be seen and appreciated in contrast to the ways in which they had been forced into a "dishonest presentation of themselves" by the pressures of the sexual, gender-identifying, and religious majority. Even as it has been updated over the years to be more inclusive, the prayer continues to celebrate the freedom that comes from ending hiding, blossoming your true self into the light.

As a straight, cis-gender woman, welcomed into this community, this prayer has grown to hold tremendous significance for me. I am humbled by the courage that it took for CBH's founders to open their space to the wider Jewish world, risking being outnumbered and subsumed by people whose experiences did not mirror their struggle. I deeply appreciate what it means to make the choice to come out into the open as your full, true self. At the same time, I have become increasingly aware of the necessity of a baseline of safety for this act to be a choice, and for that choice to bring a sense of freedom and empowerment.

Take a recent, relatively insignificant, example from my life. I decided to cut my hair short. After more than two years of pandemic lengthening, I was ready for a change.

When my kids saw the new haircut, they were not impressed. My daughter asked "why?" in a voice laden with sorrow. My son said the haircut looks "bad" and that it emphasized the newest citizens of my scalp, my gray hairs. I knew it was a big change, and that it would shift the way I present myself to the world. I would have to wear it with confidence, knowing that there are many ways to be "feminine" and it was OK to look my age. I know that I am lucky to live in a time and place (and a body) where my risks for being harassed for my fashion choices are minimal. I am "out" as a (white) Jewish woman just two years shy of her 40th birthday.

All that being said, two other recent experiences reminded me of the freedom that comes from also being able to hide, and how that freedom does not belong to everyone. This past weekend, I had the honor of attending the Marvin C. Goldstein Project Understanding Retreat for Emerging Leaders, a gathering sponsored by the American Jewish Committee (AJC)'s Atlanta Black/Jewish Coalition. The coalition has been around since 1982 when John Lewis, Sherry Frank, Cecil Alexander, and other members of Atlanta's Black and Jewish communities got together to campaign for the renewal of the Voting Rights Act. Today, the retreat is primarily about increasing "understanding of, interactions amongst, and authentic relationships between those identifying with the Black, Jewish, and Jews of Color communities."

|

| Project Understanding Class of 2022 |

A key part of fulfilling that mission involved frank conversations among the retreat's cohort of about forty Black + Jewish professionals under the age of forty. Perhaps the most intense iteration of this conversational process was the "everything you wanted to know" session on Saturday night. After listening to members of the "Black delegation" talk about how they kept their wallets in the driver's side door in case of traffic stops and crossed the street to avoid being perceived as following a white person at night, the white "Jewish delegation" was asked how white privilege functioned in our lives. (This year, the Jewish delegation was almost all white-presenting Ashkenazi with the exception of a few who were Mizrahi or Sephardic or of Asian-American heritage.) I found myself answering that white privilege meant that I could move through the world without people knowing that I was Jewish. Non-Jewish white people were not generally guarded around me. In some cases, they might openly reveal antisemitic sentiments, not directed at me at all. In essence, I could hide.

|

| One way I often reveal my Jewish identity is through wearing a Star of David necklace like this one, a duplicate of that worn by my mother and grandmother. |

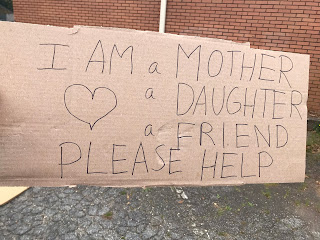

In the United States, it is impossible to hide from racism in a Black body. At the same time, it is all-too-possible not to be seen. This morning, I visited the Dignity Museum, a project of the non-profit organization Love Beyond Walls. I had the honor of hearing Terence Lester, the organization's founder, speak about his life. Lester talked about his experiences with homelessness and his experiences being mistaken for the janitorial staff at a large gathering of donors fundraising for nonprofit organizations where he was the keynote speaker. Lester spoke about the parallels between his experiences as a Black man moving in predominantly white spaces and those of people experiencing homelessness across the country. He spoke about what it was like to be feared, discounted, and stereotyped. He also spoke about the power of choice, a most basic building block of freedom.

|

| Housed in a trailer, the Dignity Museum can travel around the country. |

|

| Love Beyond Walls included excerpts from oral histories with people experiencing homelessness in their tour of the Dignity Museum as well as quotes on the wall. |

|

| Terence Lester controlled the soundscape inside the Dignity Museum with an app on his phone. |

In his final book, Where Do We Go From Here, Dr. Martin Luther King wrote about "the world house" in which we all live. We are interconnected, whether we want to be or not. Terence Lester quoted King in his explanation of the work of Love Beyond Walls. An understanding of our interconnectedness can lead to "systems thinking" which is helpful when looking to address global problems. At the same time, my experiences over the last few days have brought home to me the limitations of systems thinking. It can be easy to get caught up in a desire for big solutions to big problems. After all, the more freedom of choice we have in our lives, the more powerful we can be. And yet, when those solutions are not forthcoming, it can be easy to feel a sense of futility. If there are too many choices of actions, and none seems perfect or guaranteed to succeed, why not withdraw into our own lives? Why not hide? I am reminded that when you hide, you cannot seek. We have the freedom to see and to grant others the freedom of being seen. And those small connections turn into a web of connections more powerful than any one person can be on their own. Ironically, the power is there, even if it's too big to see.

Comments